Something is stirring again in the house of Saud. In the past two weeks, as the global health crisis intensified, Saudi Arabia’s crown prince, Mohammad bin Salman (MBS), further roiled international relations by arresting four royal relatives and engaging in a risky “global game of chicken” with Russia over oil supplies that has collapsed crude prices and shaken an already fragile world economy.

Saudiologists have scrambled to parse the headstrong crown prince’s latest moves. Some see it as further chapters in his consolidation of power, months after his father King Salman’s 84th birthday. But, in fact, what we are seeing is more evidence of the fading resilience of autocratic regimes in the Middle East—a resilience that many Western policymakers have unwisely wagered upon.

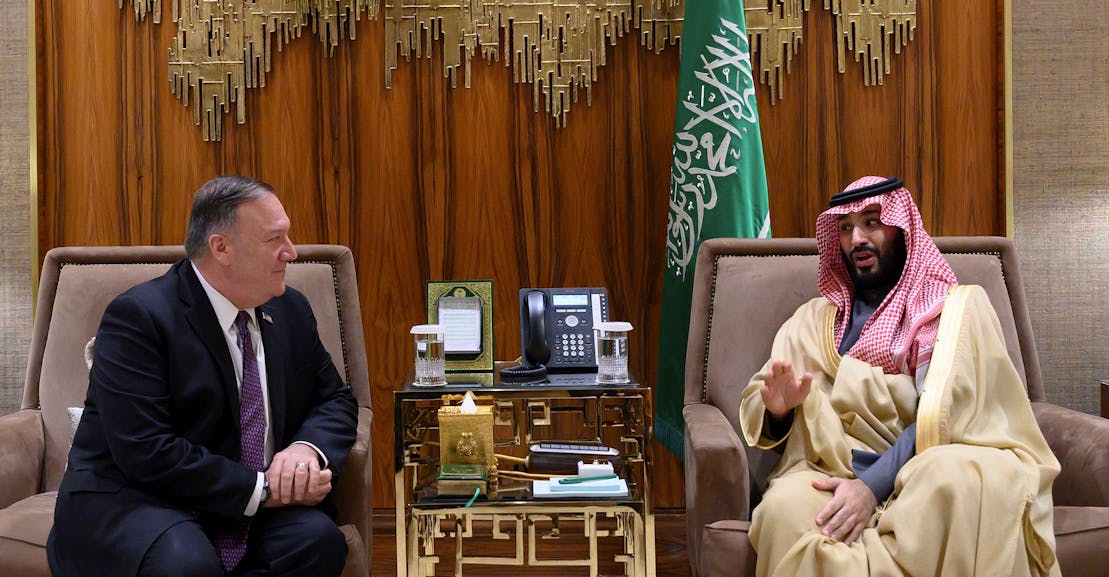

Less than a decade ago, as popular uprisings swept the Middle East, Western leaders cautiously heralded the advance of the region’s democrats; as the uprisings faltered, it did not take long for developed powers to renew their embrace of the region’s autocrats. President Trump’s enthusiasm for dictators in the Middle East is only the most recent—and the most egregious—example. It was his predecessor, Barack Obama, who gave MBS a pass to burnish his martial credentials by waging war in Yemen.

Trump has crowed about how his close relationship with Saudi Arabia has secured new sales of U.S. weapons to the kingdom. But France, Germany, and the United Kingdom have also been enthusiastic, if less boastful, arms vendors to a range of dictators across the Middle East since the Arab Spring.

The European Union has continued to proclaim its support for human rights and democracy in the region. But in 2019, it held the first E.U.-Arab League Summit in Egypt, a country descending into an even deeper authoritarian thrall than existed under deposed dictator Hosni Mubarak. The title of the summit’s declaration was “Investing in Stability.”

European and American policymakers are undoubtedly betting that the firm hand of a friendly despot is a simpler way to secure Western interests. These days, those interests mainly involve stopping perceived threats: terrorism, Iran (if you are the U.S.), and refugees (if you are Europe).

But instead of following the path of least resistance, policymakers have settled upon the route of least resilience. In Saudi Arabia, MBS’s lifting of social and religious restrictions may have won him greater support among the country’s youthful population—but it is a measure of how uncertain the crown prince is of his support that he repeatedly flinches, then flails, at the slightest perceived challenge to his authority, whether it comes from family members or independent journalists.

Likewise, MBS’s oil-price war with Russia underscores how his much-lauded reforms to wean Saudi Arabia away from its oil dependency are faltering. Why else make such a risky move to reassert Saudi power and market share in the global oil bazaar?

While such behavior risks eroding the Saudi state’s financial cushion, at least the kingdom has a cushion. The West’s other key autocratic ally in the region—President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt, who came to power through a military coup—has pursued a bleaker approach that is keeping his state solvent by impoverishing his people. The regime won plaudits from the International Monetary Fund for slashing public subsidies, but the number of Egyptians living below the poverty has grown to one-in-three. Sisi has felt compelled recently to begin placating his restive working class with salary bonuses and tax cuts.

The global economic impact of the new coronavirus will place another heavy straw on the back of the Egyptian or Saudi economies, further undermining the ability of the ruling regimes in these countries to build or sustain popular legitimacy. This is important because in the past, Middle East autocrats stayed in power through a combination of coercion and consent. The latter was largely purchased through a social contract which provided citizens with economic and social benefits in return for loyalty. Coercion could then be focused mainly on those unwilling to abide by the contract’s terms.

If consent cannot be sustained, however, then invariably an autocrat ends up relying a lot more on repression. In both Egypt and Saudi Arabia, this regressive trend is already hardening.

In Egypt, Sisi has thrown a dragnet over the entire country, arresting thousands and smothering most forms of free expression. Compared to Egypt, Saudi repression has been more surgical, with targeted—though still numerous—arrests and killings of dissidents, most infamously, Jamal Khashoggi, the Washington Post columnist, in Turkey.

Repression is hardly a new fixture in the Middle East, but this fact shouldn’t lead us to ignore the sustained and, in some cases, unprecedented ways in which repression is now being applied. The current crop of dictators, uncertain of their citizen’s regard and unsure of what other policies they can pursue to win it, are squeezing their societies to the breaking point. When this results in protest or violence, the regimes are less inclined to prudently back off, as some of their predecessors had in the past, and instead keep squeezing as hard as they can.

The result of these cycles of pressure and popular unrest is the continued and occasionally noisy fracturing of regimes and societies across the region. It is not the quiet, soothing stability that Western policymakers crave, and citizens of the region deserve.

2020-03-17 10:17:21Z

https://newrepublic.com/article/156923/perpetual-weakness-middle-east-despots

Read Next >>>>

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The Perpetual Weakness of Middle East Despots - The New Republic"

Post a Comment